Kaspersky just released antivirus software for Linux home users. $53.99 for the first year, $89.99 after that. AI-powered scans, real-time monitoring, anti-phishing—the whole nine yards.

And I’m not buying it.

Not because I’m cheap (okay, maybe a little), and not because Kaspersky is banned in the US for national security reasons (though that’s a fun conversation). I’m not buying it because the question “Do Linux users need antivirus?” is fundamentally the wrong question to ask.

The right question is: Where in your security stack does endpoint antivirus actually fit?

The Windows Reflex

Let’s talk about why this question even comes up. Windows users are conditioned—trained like Pavlov’s dogs—to believe that endpoint antivirus is the first line of defense. It’s not their fault. For decades, Windows security was Swiss cheese, and desktop AV was the only thing standing between you and total system compromise.

Boot up a Windows machine without AV, and within hours you’d have seventeen toolbars, a crypto miner, and something claiming to be a Nigerian prince living in your registry. So the industry built an entire ecosystem around endpoint protection: scan everything, all the time, trust nothing.

Then Linux users look at this ecosystem and think, “Should I be doing that too?”

Short answer: No.

Longer answer: Maybe, but probably not for the reasons you think.

Defense in Depth (And Where AV Actually Sits)

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: If malware is already executing on your local filesystem, you’ve already lost multiple layers of defense. Desktop antivirus is the last line of defense, not the first—and if you’re relying on it as your primary security strategy, you’ve fundamentally misunderstood how modern threats work.

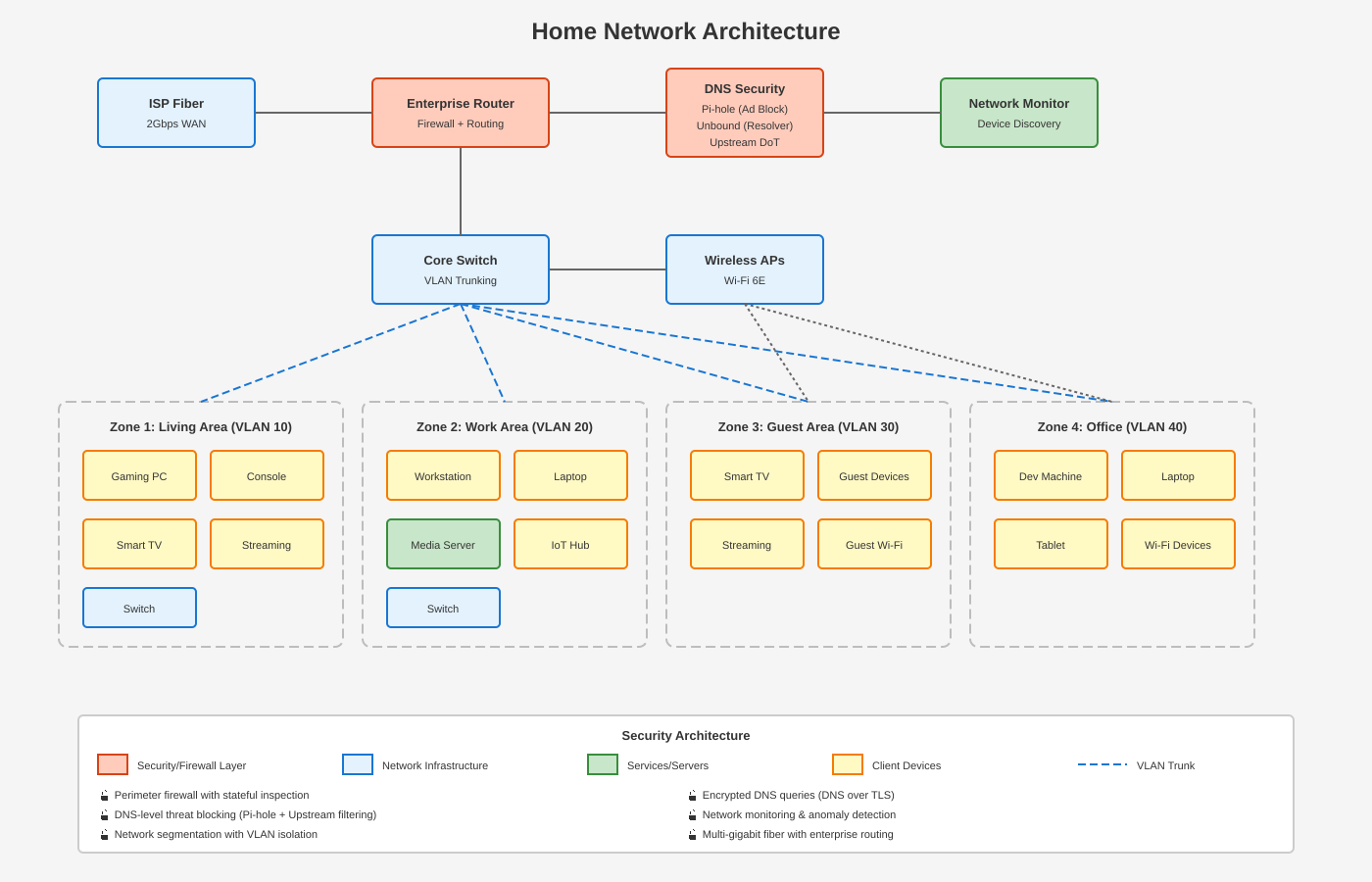

Let me show you what I mean. Here’s my home network:

This isn’t security theater. This is defense in depth, and every layer blocks entire classes of threats before they ever reach my desktop:

Layer 1: Perimeter Firewall (Enterprise Router)

Stateful packet inspection at the edge. Malicious traffic doesn’t even make it past the front door. This blocks port scans, intrusion attempts, and most network-based attacks before they reach any device on my network.

Layer 2: DNS Security Stack

This is where it gets interesting. Every DNS query on my network goes through three filters:

-

Pi-hole: Blocks ads, trackers, and known malicious domains at the DNS level. Can’t download malware from evil.com if your DNS server pretends evil.com doesn’t exist.

-

Unbound: Recursive DNS resolver that validates DNSSEC. No cache poisoning, no DNS hijacking.

-

Quad9 DNS over TLS (DoT): Encrypted DNS queries to an upstream provider that does threat intelligence filtering. Even if something slips past Pi-hole, Quad9’s threat feeds catch most of it.

This stack blocks entire attack vectors that desktop antivirus can’t even see. Drive-by downloads? Command-and-control callbacks? Phishing domains? Dead on arrival.

Layer 3: Network Segmentation (VLANs)

My network is split into four isolated VLANs:

- VLAN 10: Living area (gaming, entertainment)

- VLAN 20: Work area (workstation, media server, IoT)

- VLAN 30: Guest network (isolated from everything)

- VLAN 40: Office (dev machines, laptops)

If something does compromise a device, it’s contained. A sketchy IoT camera in VLAN 20 can’t phone home through VLAN 40’s dev machine. Lateral movement is hard when there’s no lateral path.

Layer 4: Network Monitoring

Device discovery and anomaly detection. If something starts behaving weird—sudden outbound connections, unusual traffic patterns—I know about it before it becomes a problem.

Layer 5: Operating System Security (Linux)

- Repositories are cryptographically signed

- Package managers verify checksums

- User permissions actually mean something

- No .exe files randomly executing from Downloads

- Flatpak/Snap sandboxing for untrusted applications

This is why Linux malware is rare: the entire software distribution model is fundamentally different from Windows. You’re not downloading random executables from sketchy websites—you’re pulling from trusted repositories with verified signatures.

Layer 6: Endpoint Antivirus

And here, at the very bottom of the stack, is where ClamAV or Kaspersky would sit. Scanning your local filesystem after everything above has already filtered the threats.

It’s like adding a screen door to a vault.

When AV Actually Makes Sense on Linux

I’m not saying endpoint antivirus is never useful on Linux. There are legitimate use cases:

1. Mail Servers If you’re running a mail server that services Windows clients, ClamAV makes sense. You’re not protecting yourself—you’re protecting your users from malware attachments before they reach Windows inboxes.

2. File Shares (Samba/NFS) Same deal. If you’re sharing files with Windows machines, scanning those shares prevents you from becoming an accidental malware distribution point.

3. Compliance Requirements Some industries require endpoint AV regardless of OS. If you’re in healthcare, finance, or government contracting, you might need ClamAV just to check the compliance box—even if it’s not technically necessary.

4. Extreme Paranoia (Legitimate Edition) If you’re a journalist, activist, or researcher dealing with state-level adversaries, endpoint AV might catch something custom-tailored that upstream filters don’t recognize. At that point, you’re also using Qubes OS, full-disk encryption, and air-gapped machines—so AV is just one tool in a much larger arsenal.

Notice what’s not on this list? “I browse the web and run Steam.” That’s not a threat model that requires desktop antivirus.

The Kaspersky Pitch (And Why It’s Nonsense)

Kaspersky’s marketing for this Linux AV claims that “Linux threats have increased 20-fold over the past 5 years.”

Let me translate: Server-side Linux malware targeting enterprise deployments has increased. Ransomware targeting misconfigured cloud instances, cryptominers exploiting unpatched vulnerabilities, botnets recruiting Docker containers with default credentials.

You know what hasn’t increased 20-fold? Desktop Linux malware targeting home users running an up-to-date Linux distro with Pi-hole DNS filtering.

This is classic FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, Doubt) marketing. Take a real statistic about enterprise threats, apply it to home users, and sell them a solution to a problem they don’t have.

Oh, and that $89.99/year price tag? For software that “does not meet GDPR compliance standards” (their words, not mine) from a company banned in the US for national security concerns? Hard pass.

The Real Threat Model for Linux Desktop Users

So what should you actually worry about as a Linux desktop user?

1. Social Engineering

The weakest link is always between the keyboard and chair. Phishing emails, fake “urgent security updates,” malicious browser extensions. No antivirus will save you from sudo rm -rf / --no-preserve-root if you copy-paste commands without understanding them.

2. Supply Chain Attacks Compromised upstream packages, malicious npm/pip modules, backdoored dependencies. This is where cryptographic verification and repository trust chains actually matter.

3. Browser Exploits Zero-day vulnerabilities in Chrome/Firefox. Keep your browser updated, use uBlock Origin, don’t install sketchy extensions. DNS filtering helps here too.

4. Physical Access If someone has physical access to your machine, game over. Full-disk encryption (LUKS) is your friend.

Notice what’s not on this list? “Random .exe files from shady download sites.” Because you’re not running Windows.

The Performance Cost Nobody Talks About

Here’s the other dirty secret about endpoint antivirus: it’s slow.

On-access scanning means every file operation gets intercepted, scanned, and approved before it executes. For compiling code, running VMs, or gaming (you know, the things I actually use my PC for), that overhead is measurable.

ClamAV can peg a CPU core during scans. Kaspersky’s AI-powered scanning probably does the same. For what? To catch threats that my DNS stack already blocked three layers upstream?

I’d rather spend those CPU cycles on actual work.

What I Do Instead

My security strategy is simple:

- DNS filtering (Pi-hole + Unbound + Quad9 DoT): Blocks threats at the network level

- Firewall (enterprise router): Stateful inspection at the perimeter

- VLAN segmentation: Limit blast radius if something does go wrong

- Keep everything updated: Rolling release distro means I get security patches quickly

- Don’t do stupid things: No random PPAs, no unverified scripts, no

curl | sudo bash - Monitor network traffic: If something weird happens, I’ll see it

With this setup, endpoint antivirus is redundant. I’m not leaving gaps for it to fill—I’m blocking threats at layers where they’re easier to detect and stop.

The Honest Trade-Offs

Let’s be clear about what I’m not saying:

- I’m not saying Linux is invulnerable (it’s not)

- I’m not saying you should ignore security (you shouldn’t)

- I’m not saying ClamAV is useless (it has legitimate use cases)

What I am saying is this: Understand your actual threat model before throwing money at solutions.

If you’re running a default router with ISP DNS and no network filtering, maybe ClamAV makes sense as a band-aid. But the correct solution isn’t desktop AV—it’s fixing your network security.

If you’re sharing files with Windows users, ClamAV is a courtesy. Run it.

If you’re trying to meet compliance requirements, install whatever the auditors want and move on.

But if you’re a home Linux user with proper network security, up-to-date software, and basic operational hygiene? You don’t need antivirus. You need to stop thinking like a Windows user.

The Bottom Line

Kaspersky launching a Linux antivirus isn’t about Linux users needing protection. It’s about a company expanding into a new market and banking on Windows-conditioned users who don’t understand the difference.

Linux security works differently. The repository model, permission systems, and software distribution chains are fundamentally different from Windows. The threats you face are different. The solutions should be different too.

So no, I’m not running antivirus on my Linux desktop. I’m running a properly configured network with defense in depth, DNS-level filtering, and segmentation that actually blocks threats before they reach my filesystem.

Because scanning for malware after it’s already on my disk is the wrong layer to defend. I’d rather stop it at the door.

UPDATE: Someone will inevitably comment “But what about ransomware targeting NAS devices!” Yes, that’s a thing. And if you’re running a NAS accessible from the internet without VPN access, proper authentication, and regular backups, you have bigger problems than whether you’re running ClamAV. Defense in depth means every layer matters—not just the last one.